The task at hand for branders and marketers is to learn how to serve two masters at the same time: the brands and the planet. In this article, I explain why ‘do-gooder marketing’ fails at this task and offer an alternative approach: hierophanic marketing.

This new approach, I believe, can help the industry recapture its prestige and influence while also playing a fundamental role in the sustainability movement (the ‘modern sacred’). Marketing is at its best when it’s operating from a position of power, not weakness.

Proven Systems for Business Owners, Marketers, and Agencies

→ Our mini-course helps you audit and refine an existing brand in 15 days, just 15 minutes a day.

→ The Ultimate Brand Building System is your step-by-step blueprint to building and scaling powerful brands from scratch.

Table of Contents

Why Apple’s “Mother Nature” was important

Apple’s 2023 eco-themed “Mother Nature” ad received mixed reactions. What most commentary surrounding it failed to emphasize, however, was a game-changing element this ad introduced: an element of paganism. The ad depicts a visit paid by Mother Nature – a pagan supreme deity – to an Apple board meeting and the ensuing discussion of Apple’s sustainability credentials.

It is not our objective to discuss these credentials against possible critiques of greenwashing (other commentators have scrupulously done this). The goal is to reflect on and help advance the evolution of sustainable marketing strategies by using Apple’s “Mother Nature” as a benchmark. There are two general points to be made about the campaign: a positive one and a critical one.

Apple’s approach to sustainability from an openly religious angle reflects the seriousness of climate change and other problems facing the planet. The ad’s comedic elements notwithstanding, I think Apple is sending a timely and profound spiritual message here: It doesn’t matter if we are believers or not in the traditional sense; sustainability is the ‘modern sacred’ we must all rally behind.

A critical point, however, must also be made. While the form of the ad is new, the content fits squarely into the old paradigm of ‘do-gooder marketing’ where companies shed some tears about the planet and then – uncritically – list all the sacrifices they are making to honor it. Whether you catalog your company’s planetary ‘offerings’ in a boring corporate website or a fancy video featuring an Academy Award-winning actress, the do-gooder strategy still doesn’t produce impactful marketing. It fails because it is abstract and self-referential: self-obsessed with the company’s alleged good deeds. It doesn’t include the people by showing how they can participate in the ‘modern sacred’ that is the sustainability revolution.

Apple’s Mother Nature character can thus paradoxically be seen as an impersonation of weak sustainability marketing: she’s fancy, self-righteous, and knows some tricks, but she has no real impact and is reduced to box-checking what serious people in the boardroom have to say.

By trying to be ‘good’, marketing has turned bad

Apple should be recognized for helping trailblaze a new vision of sustainability as the ‘modern sacred’, but recent campaigns from other brands have shown that marketing can serve both masters – the brand and the planet – much more efficiently.

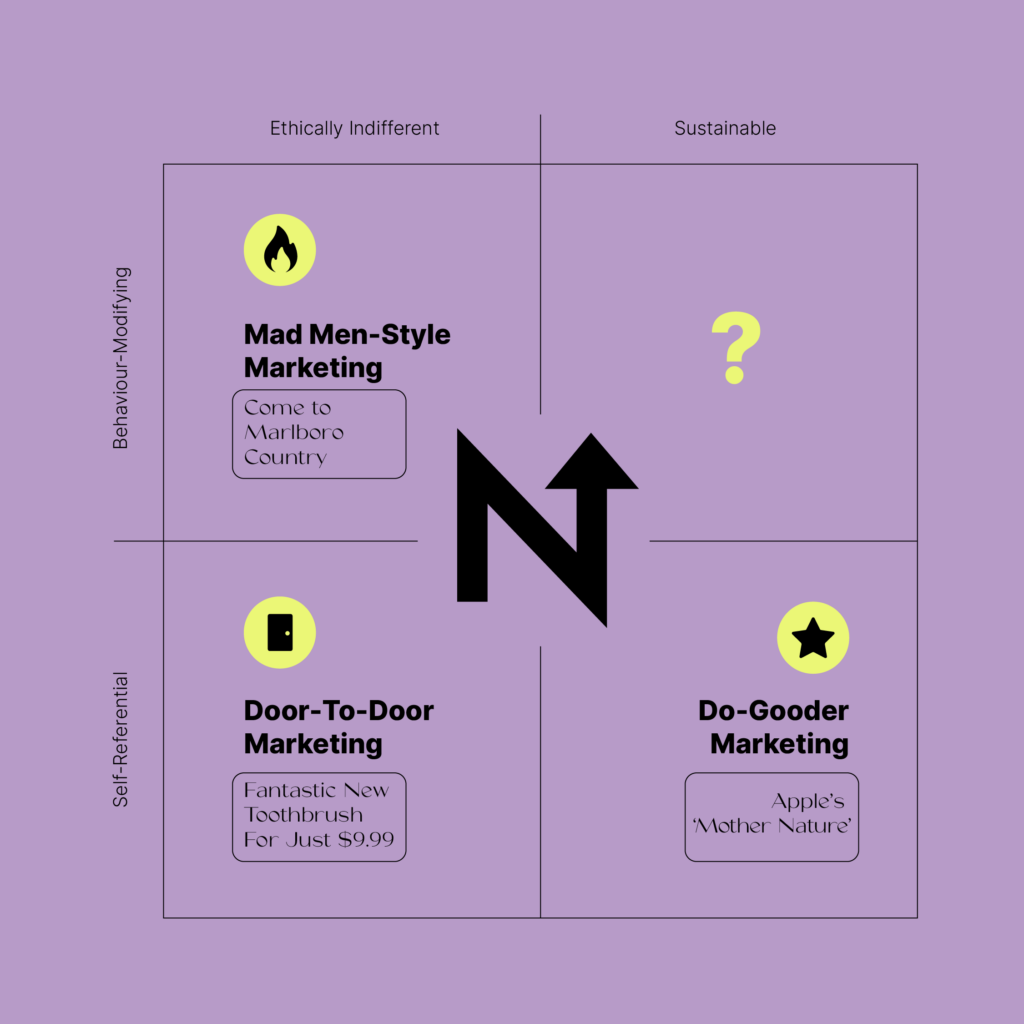

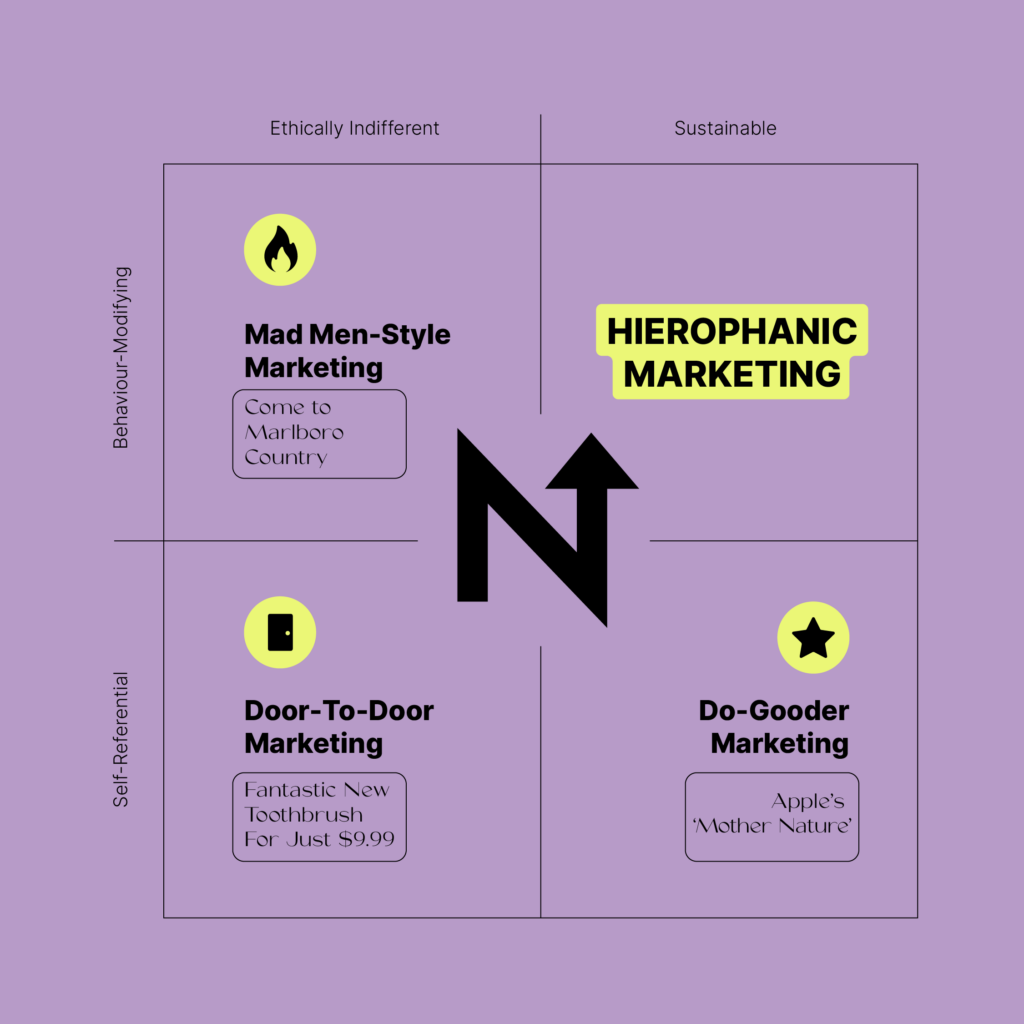

To better understand the evolution of sustainable marketing (and marketing in general), I propose using a simple 2×2 matrix where the letter N shows the direction of evolution.

By seeking a clean break from the morally questionable content of mad-men style marketing, do-gooder marketing also gives up the ambition to deeply impact consumer behavior. Instead, it retreats to the self-referential stage of marketing: just like a door-to-door salesman would tirelessly list the “remarkable features of this new fantastic toothbrush”, do-gooder marketing is reduced to the role of itemizing the company’s good deeds (eliminating plastic, shifting to clean electricity, reducing carbon emissions, etc.).

In both cases, marketing isn’t really adding value but only reporting on what’s been done on the factory floor. This, of course, doesn’t mean that sustainable business practices don’t matter (they matter immensely!). The point here, however, is that branders and marketers have always been at their best when they go beyond self-referential reporting and seek to bend the structures of how people perceive and operate within reality.

Companies don’t need marketers to tell them to be good boys and girls, and they certainly don’t place strategic importance on marketing that merely narrates (however cheesily) the eco-friendly improvements made in the manufacturing process. What businesses do need desperately, however, are new ideas. Ideas that can help them navigate between the ‘profane’ and the ‘sacred’ agendas of doing business today.

The ‘profane’ agenda is growing brand value and demand for products and services. The ‘sacred’ agenda is doing the right thing for the planet. What can be more profane than buying and consuming? What can be more sacred than protecting planet Earth? Does it mean, therefore, that these two agendas are always mutually incompatible? I don’t believe so. And that is where hierophanic marketing comes into play.

What marketers need to know about hierophanies

The concept of hierophany, borrowed from a scholar of ancient faiths Mircea Eliade (1907-1986), means a manifestation of the sacred (from Greek hiero-, “sacred,” and phainein, “to show”). I explained the concept in detail in my first article on hierophanic marketing. However, further clarifications might be helpful to position the hierophanic framework in the evolution of marketing strategies.

Crisis and spirituality

Eliade explains in No Souvenirs (1977) that spiritual experiences first appear in different cultures when people undergo a crisis and ‘realize’ that their existence is a fall from a state of golden-age perfection (one could argue that our culture is experiencing a similar realization).

At this point, a culture experiences a creative boom and develops “two modes of being in the world”: the sacred and the profane. Upon ‘realizing’ that their dull everyday existence is just one side of it (the profane), they start to look for ‘openings’ into the realm of extraordinary and supernatural, a secret timeless world infused with spiritual meaning and cosmic significance (the sacred).

Everyday objects carrying sacred messages

They discover these openings from chaos to cosmos in hierophanies – manifestations of the sacred in profane objects. Almost anything can become a hierophany: stones, animals, rivers, trees, or man-made objects like masks or ceremonial costumes. Now, as you read the following words from Eliade’s The Sacred and the Profane (1957) about hierophanies, please also think about the relationship between product and brand:

Every hierophany results from a “mysterious act – the manifestation of something of a wholly different order […] in objects that are an integral part of our natural profane world”.

That’s the double nature of all hierophanies. A sacred rain stone, for example, does not cease to be a stone, but it is worshiped because it is also more than a stone; it is a manifestation of a sacred power that can summon rain upon someone touching the stone.

In the previous article, I explained how – through the “mysterious acts” of hierophanic marketing – profane objects like jars of mayonnaise and EV charging stations can also become manifestations of the ‘modern sacred’ principles of sustainability.

Power to the people

To escape their profane existence and empower themselves, people of archaic societies would tend to live as much as possible near hierophanies. This way, Eliade teaches us, they’d get “to be, to participate in [otherworldly] reality, to be saturated with power”.

That’s why even their homes would often be transformed into hierophanies. According to a ritual in India, an astrologer would point to a spot just above the mythical underground snake before building a house. The master mason would then drive a sharpened stake through this designated area, symbolically beheading the snake. Subsequently, the foundation stone would then be placed at this precise location.

Based on scholarly interpretations, this ritual reproduces a scene in the sacred text of Rigveda where the beheading of a snake is an act of creation, an overcoming of chaos, and the birth of the sacred. By building a house following this ritual, homeowners create the world anew: they cosmicize a piece of unknown territory (chaos) and, through their agency, make a hierophany. It’s a powerful feeling to return home every night knowing your house is part of the sacred world, isn’t it?

A high-stakes role for brand strategists

In archaic cultures, the responsibility of interpreting hierophanies and guiding people between the sacred and the profane rested upon the wisest and most intuitive individuals – the spiritual leaders.

Today, this prestigious high-stakes role can and should be embraced by brand strategists and marketers – no one else is positioned, or has the necessary skillset, to profoundly influence how people perceive the things surrounding them in their daily environments.

In their 2023 book Sustainable Marketing: The Industry’s Role in a Sustainable Future, Paul Randle and Alexis Eyre write that “we have the power to help change behaviors in a way that much of the scientific data generated by our well-intentioned scientists has not”.

I believe the hierophanic method can help unleash this power.

Hierophanic marketing completes our 2×2 matrix as a type of marketing that is both sustainability-oriented and behaviour-modifying.

It can be tentatively described as a strategy that (a) helps manifest the ‘modern sacred’ principles of sustainability in everyday products and services, and (b) through these manifestations, seeks to empower people to play a more proactive role in creating a sustainable world, while also (c) allowing companies to grow brand value.

IKEA, Busch Light, and modern hierophanies

In the first article, two big brand campaigns from Hellmann’s and Renault were used as case studies of hierophanic marketing. However, this strategy can also work on a much smaller scale.

Ikea’s ‘Climate Action Station’ campaign

Consider IKEA’s “Climate Action Station” campaign. It encourages families with kids to play with IKEA packaging and use it to construct “climate symbols”: elephants, plants, wind turbines, etc.

Instead of discarding cardboard and other packaging waste, families follow IKEA’s detailed instructions to craft charming cardboard toys, while discussing climate change. IKEA also encourages parents to ask their children to do some magical thinking during the creative process: “What would they like their symbol to tell their parents, teachers, politicians?”.

These cardboard-made elephants, flowers, and wind turbines are modern hierophanies. They are manifestations of the ‘modern sacred’ principle of repurposing profane objects: pieces of packaging waste. Just like the ancient Indian ritual would help sacralize a home environment, the IKEA ritual can transform every home into a ‘modern sacred’ space – a “climate action station.” These playful hierophanies empower kids and families to make a tangible impact, learn more about climate change, and actively transform chaos (planet-threatening waste) into meaning (climate symbols).

Busch Light’s ‘A Case Against Space’ campaign

‘A Case Against Space’ campaign by Busch Light exemplifies another sub-type of hierophanic marketing. In this ad, retired astronaut Doug Hurley explains that outer space isn’t so cool after all… because you cannot drink beer out there. That’s because zero gravity transforms it into a “foamy mess.” In other words, beer, as we know it, ceases to exist once we leave planet Earth.

As someone who experienced the horror and chaos of life without beer, Hurley sends us a sobering warning: “Because we can’t drink this up there, so let’s preserve what we have down here in the name of beer”.

Hierophanies are markers of boundaries between real and sacred space on the one hand, and the nonreality of surrounding unfriendly chaos on the other. This sacralized space is always worth defending or fighting for. For example, we learn from history that in Hawaii, battles were fought over the island of Molokaʻi because, unlike the other islands, it was believed to possess the sacred power of mana.

Life isn’t as rich, real, or meaningful on a desolate island without mana…or in a cold, dark world without beer. That’s why Molokaʻi was worth fighting for, and why planet Earth is. While drinking beer won’t save the planet (despite all the donations made by Busch Light to ‘One Tree Planted’), the strategists behind this campaign have nonetheless rendered a significant service to both their client and the sustainability movement. By transforming Busch Light beers into modern hierophanies, the campaign helped manifest the ‘modern sacred’ to new audiences that may not have been receptive to the principles of sustainability in the past: if some beer lovers lacked the motivation to adopt a sustainable lifestyle before, now they have a compelling reason to do so.

That’s the power of hierophanies: the same ‘modern sacred’ can be manifested in any product or service. It all depends on the brand strategist’s creativity and imagination to effectively navigate between the sacred and the profane. Unlike do-gooder marketing, hierophanic marketing is never easy.

It goes without saying, of course, that – no matter how creative and impactful – hierophanic marketing is not about letting companies off the hook when it comes to running their businesses sustainably: just like any other company, IKEA and Anheuser-Busch should be scrutinized to the highest extent in this regard.

Concluding remarks

You may find it surprising (and, hopefully, refreshing) that our ancient and modern examples of hierophanies have little to do with the rigid way sacredness is traditionally understood and portrayed. Hierophanies are playful, engaging, empowering, and down-to-earth.

Therefore, it should not come as a surprise that we are more excited about cardboard elephants and space-hating beers than a supreme goddess in a corporate boardroom. The ancients shared our preference, too. This is what Eliade had to say in his Comparative Patterns in Religion (1958): “What is clear is that the supreme sky god everywhere gives place to other religious forms. It is a movement away from the transcendence and passivity of sky beings towards more dynamic, active, and easily accessible forms [such as] mana, orenda, wakan, animism, totemism.”

Archaic faiths were dismissive of supreme beings (usually sky gods) who were considered dei otiosi – gods who created the world but then retired and were no longer present. Because this god was inactive and distant, people had no real motive to worship him/her or make sacrifices. Thus, they would rather focus their spiritual attention on hierophanies – the tangible and inclusive manifestations of the sacred that were available in their real-life environments.

Apple’s Mother Nature also seems to be an inactive supreme goddess, a dea otiosa. Despite some show-off tricks with clouds and flowers, she’s not engaging with the consumers. She seems incapable of aiding the sustainability movement and can merely listen to what Tim Cook and his well-meaning colleagues are saying about their efforts in this regard. Steve Jobs loved Marty Neumeier’s book The Brand Gap (2003), where the brand was redefined as “What they say it is. Not what you say it is”, but the insight must have been forgotten in this case.

As I have shown in this article, sustainable marketing works better (for the brand and the planet) when it’s not self-referential but actively seeking to bend the structures of perception and behavior through hierophanies.

References

- Eliade, M. (1957) The Sacred and The Profane: The Nature of Religion (Translated by Willard R. Trask). New York: Harvest, Brace & World.

- Eliade, M. (1977)No Souvenirs, Journal.

- Eliade, M. (1958). Comparative Patterns in Religion.

- Randle, Paul, and Alexis Eyre. Sustainable Marketing. Kogan Page Publishers, 3 Dec. 2023.

- Neumeier, M. (2003). The brand gap. Berkeley, Calif. New Riders.