The launch of “New Coke” 40 years ago, in 1985, is one of the most famous case studies in the world of branding and marketing. It is also one of the biggest mistakes made by a big consumer brand, with many lessons to learn from.

On April 23 of that year, The Coca-Cola Company decided to change the formula of its most popular drink for the first time in 99 years and launch it as “New Coke”. The objective was to regain market share in the US and in the cola category – especially against Pepsi – but things didn’t go as planned.

The backlash from consumers was so huge that the company had to go back to the original Coca-Cola formula.

Let’s see what happened in detail – and most importantly, what we can learn from this.

Proven Systems for Business Owners, Marketers, and Agencies

→ Our mini-course helps you audit and refine an existing brand in 15 days, just 15 minutes a day.

→ The Ultimate Brand Building System is your step-by-step blueprint to building and scaling powerful brands from scratch.

Table of Contents

About the Brand

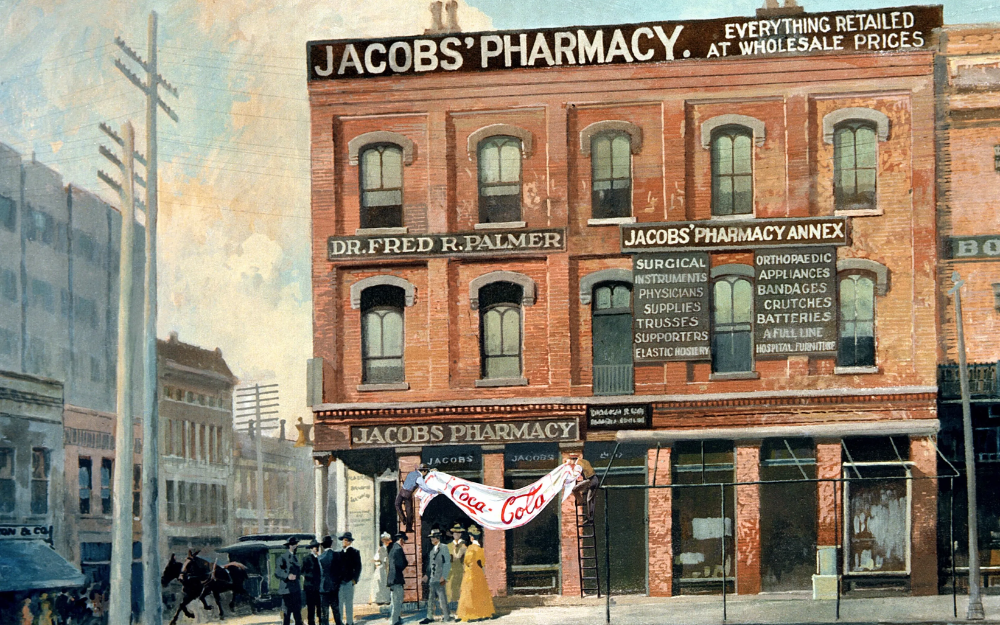

Coca-Cola was created on May 8, 1886, in Atlanta, Georgia, by Dr. John Stith Pemberton and was first sold at Jacobs’ Pharmacy for five cents a glass.[1].

Pemberton first thought of the drink as a medicine for headaches, not just a regular refreshment. He also believed it could help with hangovers. A druggist found that the syrup tasted really good when mixed with sparkling water, and that’s how Coke, as we know it, was created.[2]

By the 1930s, it had become a significant part of American culture[3], symbolizing refreshment and enjoyment. Today, Coca-Cola is a global beverage leader, operating in over 200 countries.

The Context

Many people recall what went wrong with “New Coke” but few know what the exact situation was, when the brand executives decided to reformulate the flagship product.

The Coca-Cola brand originated in the 1880s and has been enjoying its position as the leading brand in the market for many years.

In the 1970s – 1980s, the campaign “Pepsi Generation” was getting traction, and the rival brand was gaining more popularity in the US market.[4]

In the late 1970s, Coca-Cola’s leaders were focusing on legal disputes over competition rules, conflicts with bottlers over syrup prices due to inflation, debates about franchise ownership, and several failed product diversifications. All of this led them to focus less on the marketing and sales of their main product.[5]

According to Harward Business School’s case study, at that time, Coke’s growth slowed significantly from 15% per year to about 2%, and by 1980, Pepsi surpassed Coke in supermarket sales for the first time, taking 29.3% of the market while Coke had 29%.

Two years before the release of Coca-Cola’s new product, Pepsi partnered with Michael Jackson for a $5 million deal. In 1984, Michael Jackson’s commercial contributed to the brand’s success, and Pepsi reported $7.7 billion in sales.[6] In addition, Pepsi had launched “the Pepsi Challenge”, a popular campaign in which blind tests revealed that the majority of participants preferred the taste of Pepsi over Coca-Cola.[7]

In addition to this, Coke faced other challenges as industry forecasts predicted slower growth due to aging consumers choosing healthier drinks. Coca-Cola’s market research showed a decline in brand loyalty (exclusive Coke drinkers dropped from 18% in 1972 to 12% in 1982). Meanwhile, Pepsi’s exclusive drinkers increased from 4% to 11% over the same period, a tendency that was also reflected in market share trends during the same period.[8]

While the company was still number one at the time[9], Pepsi was cutting into Coke’s market share. This decrease accelerated when the Michael Jackson campaign started. Overall, Coke executives had strong concerns about consumer preference and brand awareness which were both decreasing for Coke.[10]

The Branding Objectives

With this context in mind, The Coca-Cola Company decided that something had to be done in order to regain market shares and re-invigorate the brand. The main objective was therefore to ensure Coca-Cola remained number one in the market and to do something against the increasing rise of its main competitor.

Despite spending more on ads, running a strong marketing campaign, and having better distribution and competitive pricing, the brand was still losing customers. With no clear reason for the decline, Coca-Cola’s executives started to question whether the problem was the product itself.[11] Taste tests like the Pepsi Challenge suggested that consumer preferences were changing, leading Coke to reconsider its long-standing formula.

The Market Research

In 1982, Coca-Cola surveyed 2,000 people in 10 major cities to see how they would react to a new Coke formula. Participants viewed mock ads and answered questions about whether they would try, switch to, or be upset by the change. Results showed that 10-12% of Coke drinkers would be unhappy (half of these would eventually accept it, the other half not), while some Pepsi drinkers were also interested. However, focus groups revealed strong opposition from loyal Coke fans, though researchers dismissed this as a minority opinion.

Despite these mixed reactions, Coca-Cola developed a new, sweeter, and smoother formula in 1984 after nearly 200,000 taste tests showed that people preferred the new version they’ve created.[12] A small committee, including five top Coke executives, oversaw the research. After the first research conducted on 100,000 people, CEO Roberto Goizueta kept asking if there was any flaw in the data. To be certain, Coca-Cola hired a second research firm and spent over $1 million to repeat another 100,000 tests. The results came back the same: Consumers still preferred the new formula by a margin of 53-47. Confident in the numbers, Coca-Cola moved forward and launched New Coke.[13]

But the taste tests didn’t reveal the deep emotional bond people had with the original Coca-Cola—something consumers weren’t willing to give up.

It is important to note that Coca-Cola first considered selling both the old and new Coke, but they decided not to do it because of concerns from bottlers and stores. Bottlers wouldn’t want the hassle of making two different products, and stores wouldn’t want to use their limited space to stock both versions. An executive pointed out that if a restaurant chain like McDonald’s would switch to the new Coke while the old version was still available, it could hurt the brand’s image. He believed that only the best version of the drink should carry the brand’s name.[14]

The Launch of New Coke

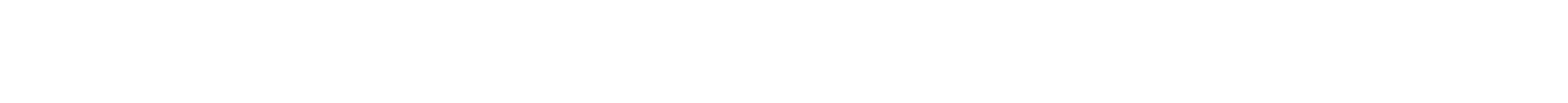

On April 23, 1985, Coca-Cola announced a change to its nearly century-old secret formula, introducing a smoother, sweeter version of the drink. [15]

The new formula was officially launched as “Coke,” though the word “New” appeared on bottles and cans, leading to the unofficial name “New Coke.” [16] The packaging was also redesigned with silver and red colors to highlight the change.

The brand launched a campaign to promote the new product, featuring Bill Cosby as the spokesperson. Ads focused on comparing the new formula to the old one to highlight its better taste, and also included updated “Coke Is It” commercials.

The taste was similar to Diet Coke but sweetened with corn syrup. Market researchers and pollsters were confident it would be a success.

As mentioned earlier, Coca-Cola executives made this change in response to competition, marking the most significant reformulation of the drink since the removal of coca leaf extracts as an ingredient in the early 1900s.

Watch the Original 1985 “CBS Evening News” report on the new Coke here.

The Public’s Reaction: Protests, Panic, and Phone Calls

The launch of New Coke in April 1985 triggered an immediate and intense backlash. The press coverage was extensive, and people quickly called it “the biggest marketing blunder of all time”.[17]

According to Coca-Cola itself, many people panicked or got depressed.[18]

“When the taste change was announced, some consumers panicked, filling their basements with cases of Coke®. A man in San Antonio, Texas, drove to a local bottler and bought $1,000 worth of Coca‑Cola. Some people got depressed over the loss of their favorite soft drink. Suddenly everyone was talking about Coca‑Cola, realizing what an important role it played in his or her life.”

Calls flooded Coca-Cola’s offices. By June 1985, the company was still receiving 1,500 calls a day—four times more than usual. And people didn’t just complain; they also took action. Groups like the Society for the Preservation of the Real Thing and the Old Cola Drinkers of America (which claimed 100,000 members) formed to demand the return of the original Coke. In Atlanta, protesters even carried signs that read, “We want the real thing” and “Our children will never know refreshment.”[19]

The outrage spread across the country. CBS News reporter Bob Simon described it as “the people against the corporation—only in America.” In California, fans gathered signatures, while in Seattle, they set up a protest hotline. One man, Gay Mullins, led the charge. As head of Old Cola Drinkers of America, he spent $30,000 of his own money and three weeks of his time fighting to bring back the original formula[20]. He believed Coca-Cola had betrayed its customers, told a reporter for People back then:

“How can they do this? They were guarding a sacred trust! Coca-Cola has tied this drink to the very fabric of America – apple pie, baseball, the Statue of Liberty. And now they replace it with a new formula, and they tell us just to forget it. They have taken away my freedom of choice. It’s un-American!”

In terms of the taste, food critic Mimi Sheraton wrote in a Time magazine review that “ “New Coke seems to retain the essential character of the original version … It tastes a little like classic Coca-Cola that has been diluted by melting ice”. [21]

The Impact on Coca-Cola’s Sales and The Brand’s Reaction

The return of the original formula came at a cost. Coca-Cola lost millions in research and advertising but gained a huge amount of free publicity, strengthening its position as a market leader.

Even though many customers complained through calls and letters, sales and surveys showed a different story. By June, 150 million people had tried New Coke. The new product was still winning over Pepsi in blind taste tests and was slightly preferred over the classic formula. 75% percent of people who tried it said they would buy it again, Coca-Cola’s brand rating went higher than Pepsi’s, sales were growing twice as fast as the year before, and bottlers were selling more than the previous years. The brand continued to respond to negative reactions but focused on increasing their sampling actions instead of advertising budgets.[22]

Considering these figures, it’s understandable that experts predicted New Coke would succeed.

However, things changed when the old version of Coke completely disappeared from the shelves. According to Harward Business School, customer complaints surged, with 8,000 calls a day, and by July, only 30% of surveyed people said they liked the new version. Sales started slowing, media coverage of the backlash grew, and Coca-Cola’s executives were shocked by how emotional customers were about losing the original formula.

Despite this, the brand decided to wait and see how sales performed over the first weekend of July, but the results were disappointing. Meanwhile, Pepsi took advantage of the situation, running ads claiming Coke had changed its formula because people preferred Pepsi.

Back to The Classic Formula

Precisely 79 days after the launch of New Coke, on July 11, 1985, the Coca-Cola Company officially announced they would bring the ‘old’ product recipe back to the shelves.

The news made headlines across the country. Consumers celebrated the decision, and in just two days, Coca-Cola received 31,600 phone calls on their hotline. It became clear that Coca-Cola was more than just a drink—it was a part of American culture.

Coca-Cola Classic didn’t replace New Coke right away. Both formulas were sold at the same time, with separate advertising campaigns. Coca-Cola Classic leaned into nostalgia with its “Red, White and You” campaign, while New Coke targeted younger audiences with the upbeat “Catch the Wave” ads.[23]

In this press conference, Coca-Cola’s executives explained the decision, saying they underestimated the passion and sense of patriotism for the brand and apologized for this mistake. Coca-Cola’s president ended his speech by saying: “It only means what we say that our boss is the consumer. Some critics will say “Coca-Cola has made a marketing mistake” and some cynics say that we planned the whole thing. The truth is: we’re not that dumb, and we’re not that smart”.

What Happened to New Coke?

Although New Coke was not well received, it remained available for several years. In 1992, it was rebranded as Coke II but never gained much popularity. With low sales and little demand, the drink was officially discontinued in 2002.[24]

However, a Stranger Things collector’s edition featuring two cans of New Coke could be purchased on Amazon for $39.99 a few years ago.

Final Outcomes

In the end, Coca-Cola achieved its main goal—reaffirming its dominance in the cola market—but not in the way it originally planned. The launch of New Coke in 1985 was a failure, sparking widespread consumer backlash.

However, this misstep ultimately reinforced Coca-Cola’s brand identity and deepened consumer loyalty, proving that even branding disasters can be turned into long-term success if managed correctly.

Today, nearly 40 years later, Coca-Cola remains a market leader, showing that learning from mistakes is just as important as avoiding them.

Key Lessons & Takeaways for Marketers & Brand Strategists

Coca-Cola’s New Coke launch is one of the most well-known marketing failures in corporate history. But the reason we love to analyze these case studies is because there is so much we can learn from them.

Like Tropicana’s packaging redesign, Gap’s new logo, or Vegemite’s product extension, New Coke is a classic case study that offers many insights for marketers and brand strategists.

Here are the key insights and takeaways:

1. Brands like Coca-Cola That Shape Culture Need to Protect Their Heritage

When they changed their main product’s formula, Coca-Cola had been part of American culture for nearly 100 years. Coke was already part of Americans’ daily lives and deeply tied to American culture. When brands have this much influence on culture, they must be extra careful with modifications related to their story and legacy since any change can affect not just customers but society as a whole.

Pepsi-Cola USA’s CEO Roger Enrico said it well [25]:

“I think, by the end of their nightmare, they figured out who they really are. Caretakers. They can’t change the taste of their flagship brand. They can’t change its imagery. All they can do is defend the heritage they nearly abandoned in 1985.”

2. Customers Own the Brand, Not the Company

Coca-Cola believed it could dictate change, but consumers fiercely defended what they saw as their brand. This highlights a timeless truth: businesses may create products, but customers ultimately define their meaning and value. Ignoring this reality can damage consumer trust and brand equityBrand equity represents the value of a brand. It is the difference between the value of a branded product and the value of that product without that brand name attached to it.. A Coca-Cola spokesperson told CBS News[26]:

“Thirty years ago, we introduced New Coke with no shortage of hype and fanfare. And it did succeed in shaking up the market. But not in the way it was intended. When we look back, this was the pivotal moment when we learned that fiercely loyal consumers -not the company – own Coca-Cola and all of our brands. It is a lesson that we take seriously and one that becomes clearer and more obvious with each passing anniversary.”

3. A Brand Lives in Its Product

People often disassociate the product from the brand, but the reality is that a product is the most tangible representation of a brand itself. It is part of its identity and not just something the company sells.

Classic Coke was a drink with a specific taste, but also the taste of what the brand is. By changing the product’s formula, Coca-Cola’s executives modified the brand and the entire experience around it. When a product is deeply tied to a brand’s identity, any change must be handled carefully to avoid breaking consumer trust.

And this leads us to the next point:

4. Sensory Identity Is Key for Food & Beverage Brands

For food and beverage companies, taste is a core part of brand identity. By launching New Coke, Coca-Cola changed the flavor of its most iconic product, disrupting what made it special to consumers.

Even though blind taste tests showed people liked New Coke better, they still rejected it because it modified a familiar and nostalgic experience. Sensory elements—taste, smell, texture—are powerful brand assets that should be handled carefully.

5. A Brand Must Always Deliver Its Promise

Coca-Cola had always marketed itself as “the real thing”. “The Real Thing” meant Coca-Cola was the original, authentic cola that people could trust and had become a genuine part of American life, unlike its competitors.

But by replacing its original formula, it contradicted that brand promise. Consumers felt betrayed because the brand no longer aligned with what they expected. This feeling of betrayal can spike very strong emotions amongst the brand’s audiences.

6. Customer Loyalty Is Highly Emotional

Coca-Cola assumed that because people preferred the taste of New Coke in blind tests, they would embrace the change. An enhancement of the product’s experience could have been a positive change.

But taste wasn’t the only factor; people had an emotional connection to the original formula. Consumers can buy based on rational reasons, but also based on feelings, memories, and habits. Marketers must always consider emotional loyalty and not just product performance.

7. Innovation Should Add, Not Replace (The Freedom of Choice Factor)

New Coke might have been more accepted if it had been introduced as an option rather than a replacement. People resist having their choices taken away—especially when it comes to beloved products.

In this case, people didn’t resist the change itself—they resisted having their choices taken away. It is this “freedom of choice” highly linked to the brand’s cultural impact that was causing such reactions. Protests increased when the original Coke stopped being available on shelves, and stopped as soon as it was brought back alongside the new one.

This case study illustrates how removing a familiar product can trigger psychological reactance, causing customers to push back, not necessarily because they dislike the new option, but because they feel forced into it. For marketers, this proves that successful innovation should expand options rather than eliminate existing favorites.[27]

8. Sales Don’t Always Equal Long-Term Success

New Coke sold well at first—75% of people who tried it said they would buy it again, and sales grew faster than the previous year. But in the end, this didn’t mean consumers accepted the change.

The backlash showed that short-term numbers don’t always reflect long-term brand health. A product can sell well initially but still damage a brand if it weakens customer trust and loyalty over time.

9. Strong Market Research Requires Emotional Insights

Coca-Cola relied heavily on blind taste tests and surveys that showed people preferred New Coke’s flavor. However, they failed to consider emotional loyalty and real-world behavior. While data suggested people liked the new taste, focus groups revealed passionate resistance from loyal drinkers—insights that were ignored, although they were indicators of broader backlash.

This demonstrates that market research should go beyond rational preferences and consider emotional attachment, nostalgia, and cultural symbolism.[28]

10. The Power of Social Influence To Shape Brand Perception

The company underestimated how much their most loyal (and angry) customers could influence people, leading to more and more people feeling upset about the change over time.

Marketers must ensure that research considers both majority trends and deeply committed customer segments, as these voices can often shape brand perception more than general consumer sentiment. [29]

11. A Branding Failure Can Become a Marketing Opportunity

Despite being widely mocked as an “epic failure,” the New Coke fiasco ultimately strengthened Coca-Cola’s brand in an unexpected way. When the company brought back the original formula as “Coca-Cola Classic,” it reinforced customer loyalty and boosted sales beyond previous levels.

So by admitting mistakes, listening to customers, and responding humbly, we see that it is possible to rebuild trust and brand loyalty.

References

[1] The Coca-Cola Company (2024). The Birth of a Refreshing Idea . [online] www.coca-colacompany.com. Available at: https://www.coca-colacompany.com/about-us/history/the-birth-of-a-refreshing-idea.

[2] Fournier, S. (1999). Introducing New Coke. [online] Harward Business School. Available at: https://store.hbr.org/product/introducing-new-coke/500067

[3] Fogarty, K. (2018). New Coke | History, Response, & Facts. In: Encyclopædia Britannica. [online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/New-Coke.

[4] Newsdesk, M. (2009). Branding blunders: Lessons from the ‘New Coke’ marketing disaster. [online] MyCustomer. Available at: https://www.mycustomer.com/marketing/strategy/branding-blunders-lessons-from-the-new-coke-marketing-disaster.

[5] Fournier, S. (1999). Introducing New Coke. [online] Harward Business School. Available at: https://store.hbr.org/product/introducing-new-coke/500067

[6] Ritschel, C. (2020). 35 years on: How ‘New Coke’ almost ruined Coca-Cola. [online] The Independent. Available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/food-and-drink/new-coke-coca-cola-failed-product-launches-history-a9479116.html.

[7] Fogarty, K. (2018). New Coke | History, Response, & Facts. In: Encyclopædia Britannica. [online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/New-Coke.

[8] Fournier, S. (1999). Introducing New Coke. [online] Harward Business School. Available at: https://store.hbr.org/product/introducing-new-coke/500067

[9] Haoues, R. (2015). Coca-Cola’s PR disaster, 30 years later. [online] Cbsnews.com. Available at: https://www.cbsnews.com/news/30-years-ago-today-coca-cola-new-coke-failure/.

[10] The Coca-Cola Company (2024). New Coke: The Most Memorable Marketing Blunder Ever? [online] www.coca-colacompany.com. Available at: https://www.coca-colacompany.com/about-us/history/new-coke-the-most-memorable-marketing-blunder-ever.

[11] Fournier, S. (1999). Introducing New Coke. [online] Harward Business School. Available at: https://store.hbr.org/product/introducing-new-coke/500067

[12] The Coca-Cola Company (2024). New Coke: The Most Memorable Marketing Blunder Ever? [online] www.coca-colacompany.com. Available at: https://www.coca-colacompany.com/about-us/history/new-coke-the-most-memorable-marketing-blunder-ever.

[13] The Inside History of the ‘New Coke’ Debacle. (2017). Bloomberg.com. [online] November 3 Available at: https://www.bloomberg.com/view/articles/2017-11-03/the-inside-history-of-the-new-coke-debacle.

[14] Fournier, S. (1999). Introducing New Coke. [online] Harward Business School. Available at: https://store.hbr.org/product/introducing-new-coke/500067

[15] Haoues, R. (2015). Coca-Cola’s PR disaster, 30 years later. [online] Cbsnews.com. Available at: https://www.cbsnews.com/news/30-years-ago-today-coca-cola-new-coke-failure/.

[16] Fogarty, K. (2018). New Coke | History, Response, & Facts. In: Encyclopædia Britannica. [online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/New-Coke.

[17] Fogarty, K. (2018). New Coke | History, Response, & Facts. In: Encyclopædia Britannica. [online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/New-Coke.

[18] The Coca-Cola Company (2024). New Coke: The Most Memorable Marketing Blunder Ever? [online] www.coca-colacompany.com. Available at: https://www.coca-colacompany.com/about-us/history/new-coke-the-most-memorable-marketing-blunder-ever.

[19] The Coca-Cola Company (2024). New Coke: The Most Memorable Marketing Blunder Ever? [online] www.coca-colacompany.com. Available at: https://www.coca-colacompany.com/about-us/history/new-coke-the-most-memorable-marketing-blunder-ever.

[20] Ritschel, C. (2020). 35 years on: How ‘New Coke’ almost ruined Coca-Cola. [online] The Independent. Available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/food-and-drink/new-coke-coca-cola-failed-product-launches-history-a9479116.html.

[21] Gould, R.G., Skye (2015). This mistake from 30 years ago almost destroyed Coca-Cola. [online] Business Insider. Available at: https://www.businessinsider.com/new-coke-the-30th-anniversary-of-coca-colas-biggest-mistake-2015-4.

[22] Fournier, S. (1999). Introducing New Coke. [online] Harward Business School. Available at: https://store.hbr.org/product/introducing-new-coke/500067

[23] The Coca-Cola Company (2024). New Coke: The Most Memorable Marketing Blunder Ever? [online] www.coca-colacompany.com. Available at: https://www.coca-colacompany.com/about-us/history/new-coke-the-most-memorable-marketing-blunder-ever.

[24] Fogarty, K. (2018). New Coke | History, Response, & Facts. In: Encyclopædia Britannica. [online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/New-Coke.

[25] Fogarty, K. (2018). New Coke | History, Response, & Facts. In: Encyclopædia Britannica. [online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/New-Coke.

[26] Haoues, R. (2015). Coca-Cola’s PR disaster, 30 years later. [online] Cbsnews.com. Available at: https://www.cbsnews.com/news/30-years-ago-today-coca-cola-new-coke-failure/.

[27] Jones, K., Ondracek, J., Saeed, M. and Bertsch, A. (2016). Don’t Mess with Coca-Cola: Introducing New Coke Reveals Flaws in Decision-Making within the Coca-Cola Company. International Journal of Management Research, 4(10).

[28] Jones, K., Ondracek, J., Saeed, M. and Bertsch, A. (2016). Don’t Mess with Coca-Cola: Introducing New Coke Reveals Flaws in Decision-Making within the Coca-Cola Company. International Journal of Management Research, 4(10).

[29] Jones, K., Ondracek, J., Saeed, M. and Bertsch, A. (2016). Don’t Mess with Coca-Cola: Introducing New Coke Reveals Flaws in Decision-Making within the Coca-Cola Company. International Journal of Management Research, 4(10).